The bones of the axial skeleton constitute the central bony core of the body.

Table of Contents

The Skull

It rests upon the upper end of the vertebral column and its bony structure is divided into two parts viz., cranium and face.

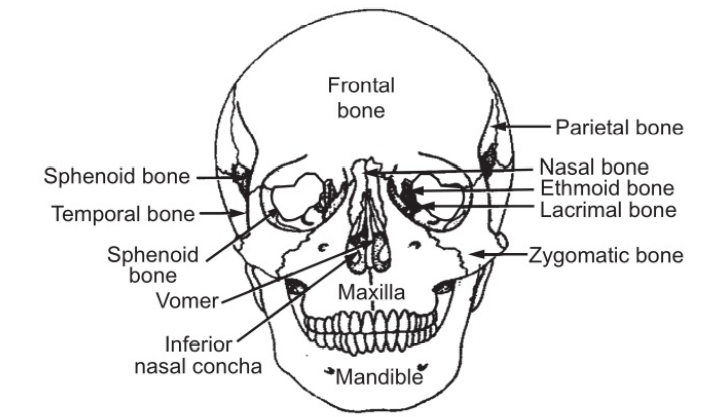

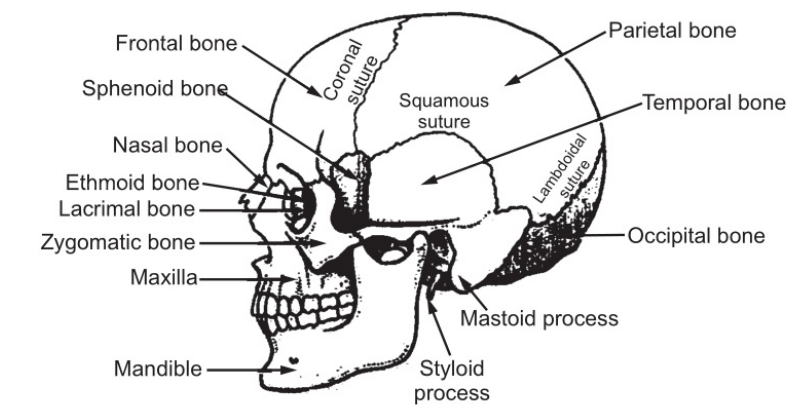

Cranium: It provides bony protection to the brain. It is described in two parts: base and vault. The base is a part on which the brain rests and the surrounding part is termed as the vault. The base is divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae. The inner surfaces of all the cranial bones are supplied with blood vessels. The bones which form the cranium [Fig. 1.1 (a) and (b)] are one frontal bone; two parietal bones; one occipital bone; one sphenoid bone; one ethmoid bone and two temporal bones.

Fig 1.1

- The Frontal Bone:

The frontal bone is a large flat bone that forms the forehead and also the upper part of the orbital cavities. It develops in two parts which gradually fuse into one bone. It contains two cavities called the frontal sinuses which lie one over each orbit. They contain air which enters by a small opening leading from nasal cavities. These sinuses give lightness to the bone and resonance to the voice, acting as sounding chambers.

- The Parietal Bones:

The parietal bones are two flat bones forming the sides and roof of the skull. They articulate with each other and with frontal, occipital, and temporal bones. The inner surface is concave and is grooved by the brain and blood vessels.

- The Occipital Bone:

The occipital bone forms the back of the head and part of the base of the skull. It forms immovable joints with parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones. On the outer surface, there is a roughened area called occipital protuberance. In this bone, there is a large opening known as the foramen magnum, for the passage of the spinal cord.

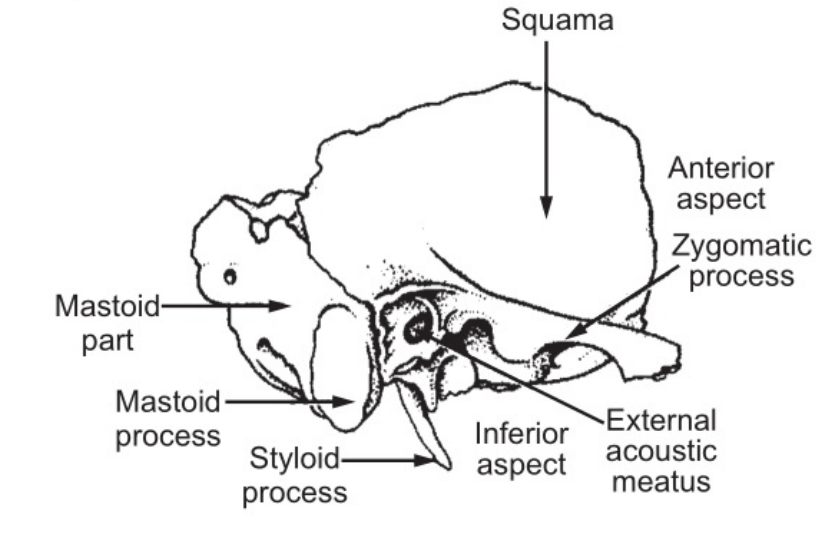

- The Temporal Bones:

The temporal bones lie on each side of the head (Fig. 1.2). Each temporal bone is divided into four parts.

They are:

(1) The squamous part is the fan-shaped portion.

(2) The mastoid process is a thickened part of bone and can be felt just behind the ear. It contains a large number of small air sinuses which communicate with the middle ear. A styloid process projecting from it gives attachment to muscles.

(3) The petrous portion is thick and forms a part of the base or floor of the skull and contains the organ of hearing.

(4) The zygomatic process is directed forward and articulates with the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch.

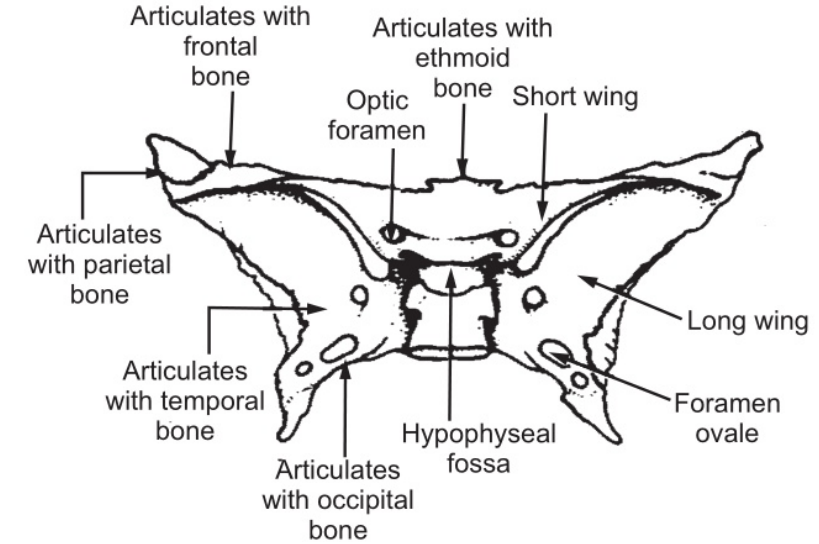

- The Sphenoid Bone:

The sphenoid bone is irregular in the shape of a bat with its wings outstretched and lies in the center of the base of the skull (Fig. 1.3). On the superior surface of the middle of the bone, there is a depression in which the pituitary gland rests. The wings are perforated by many openings for the passage of nerves and blood vessels.

- The Ethmoid Bone:

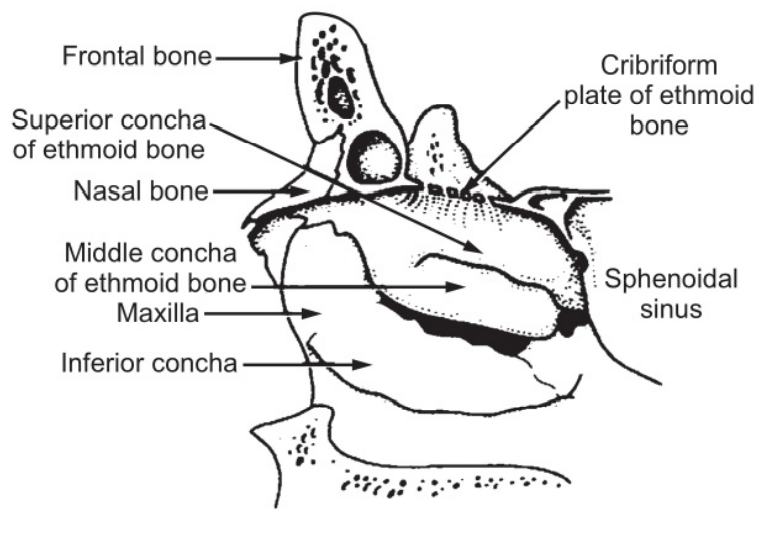

The ethmoid bone is a very light, fragile, irregular bone and occupies an anterior part of the base of the skull and helps to form the orbital cavity, the nasal septum, and the lateral walls of the nasal cavity (Fig. 1.4).

It has a horizontal flattened part called cribriform plate which has many fine openings like a sieve. The openings are for the passage of the nerves of smell called the olfactory nerves. It also contains a flat vertical portion between the two nasal cavities. Two spongy portions form an outer wall of the upper part of the nasal cavity and the inner wall of the orbit. On each side, the spongy portions present two projections into nasal cavities which are called turbinated processes. The spongy portions contain several air cavities which communicate with the nose.

The Face

Thirteen bones form the skeleton of the face. They are two zygomatic or cheekbones; one maxilla; two nasal bones; two lacrimal bones; one vomer, two palatine bones; two inferior conchae or turbinated bones, and one mandible (Fig. 4.1).

Each zygomatic bone forms the prominence of the cheek and part of the floor and lateral walls of the orbital cavity. It articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form a zygomatic arch.

Maxilla or upper jaw bone forms the upper jaw, the anterior part of the roof of the mouth, the lateral walls of the nasal cavities, and part of the floor of orbital cavities. It presents the alveolar ridge which projects downwards and carries the upper teeth. On each side, there is a large air sinus, the maxillary sinus which is lined with ciliated mucous membranes and communicates with the nasal cavity.

The nasal bones are two small bones that form the greater part of the lateral and superior surfaces of the bridge of the nose. They articulate with each other medially.

The lacrimal bones are two very small bones located in a position posterior and lateral to the nasal bones. They also form the inner wall of the orbit. They are grooved and the groove contains lacrimal sac and nasal duct. It carries tears or lacrimal fluid from the eye down to the nasal cavity.

The vomer is a thin flat bone that extends upwards from the middle of the hard plate to separate the two nasal cavities.

The palatine bones are two irregular bones that form the back of the hard palate and extend up to the outer wall of the nasal cavity into the floor of the orbit.

The turbinate bones are two small scroll-shaped flat bones that form a part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity.

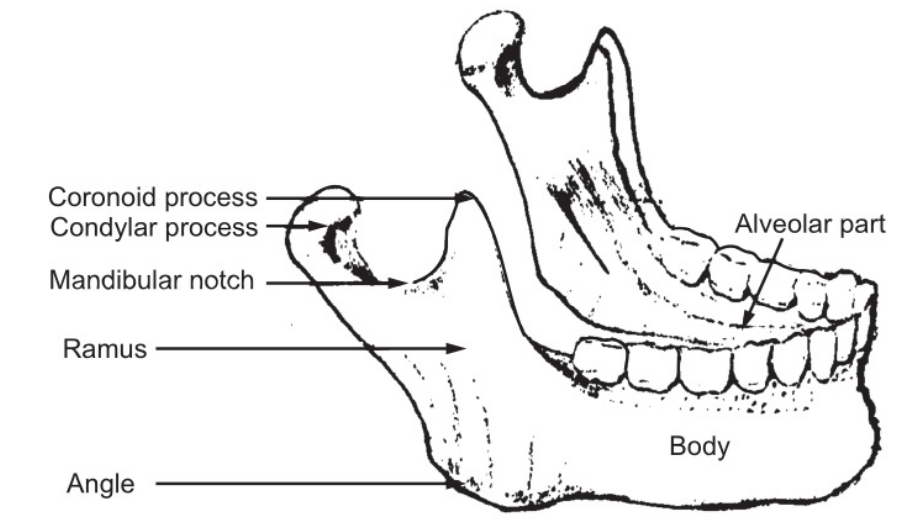

The mandible is the strongest bone of the face and is the only movable bone of the skull. It has two identical parts.

Each part consists of

- A curved body on the superior surface of which there is the alveolar ridge containing the lower teeth and

- A ramus which projects upward (Fig. 1.5). At the upper end, the ramus is divided into two processes; the condyloid process which articulates with the temporal bone, and the coronoid process which gives attachment to muscles and ligaments. The point where the ramus joins the body is called the angle of the jaw.

The hyoid is an isolated horseshoe-shaped bone lying in the soft tissue of the neck. It lies at the base of the tongue and gives attachment to the tongue muscle. It does not articulate with any other bone of the head or trunk but is attached to the styloid process of the temporal bone by ligaments.

The Vertebral Column

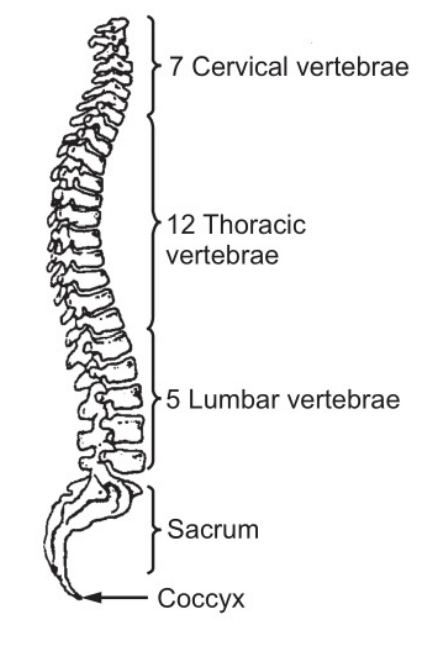

It consists of twenty-four separate, movable, irregular bones called vertebrae which are divided into three groups viz.; cervical (seven); thoracic (twelve), and lumbar (five). (Fig. 1.6). In addition, the sacrum consists of five fused bones, and the coccyx consists of four fused bones which also form a part of the vertebral column. When viewed from the side, the vertebral column shows four anteroposterior curves. They are the cervical curve, in the neck which is convex forwards; thoracic curve, convex backward; lumbar curve, convex forwards and the pelvic curve convex backward. Posteriorly convex curves, thoracic and pelvic, are called primary curves and anteriorly convex curves are called secondary curves.

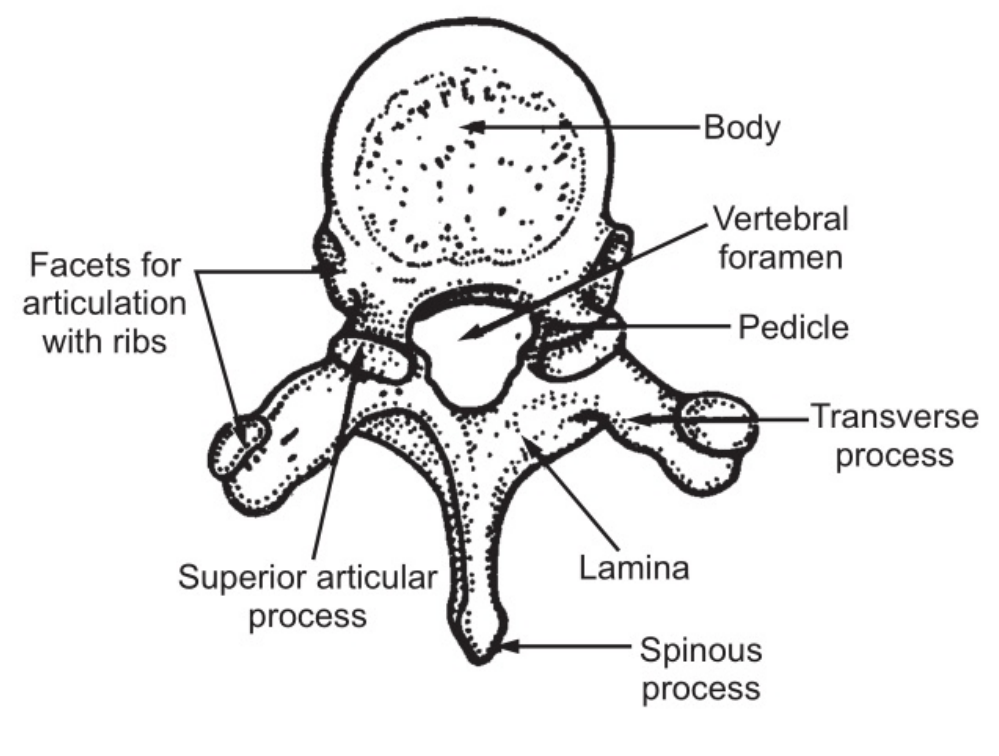

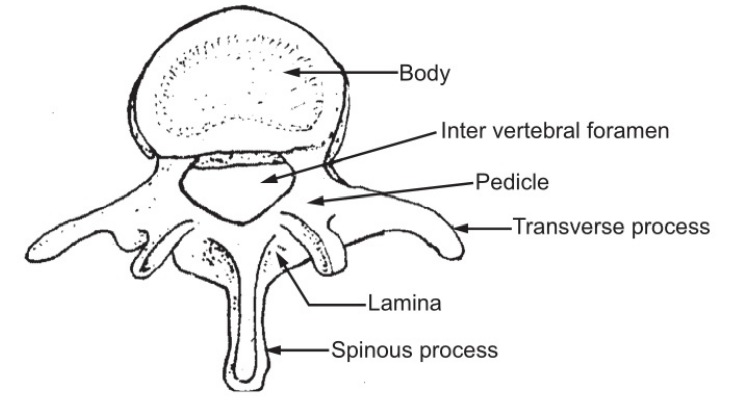

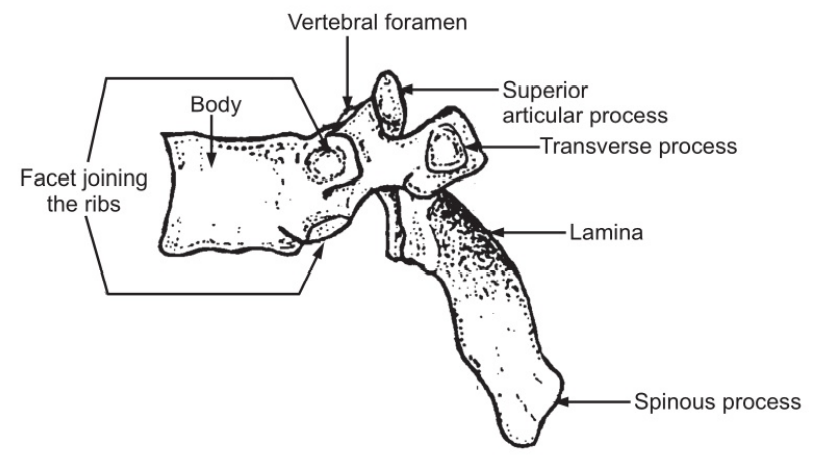

Each vertebra consists of:

- A disc-shaped body lying in the front

- An arc of bone points backward from the body and encloses a space between body and arch called the neural or spinal canal through which the spinal cord passes.

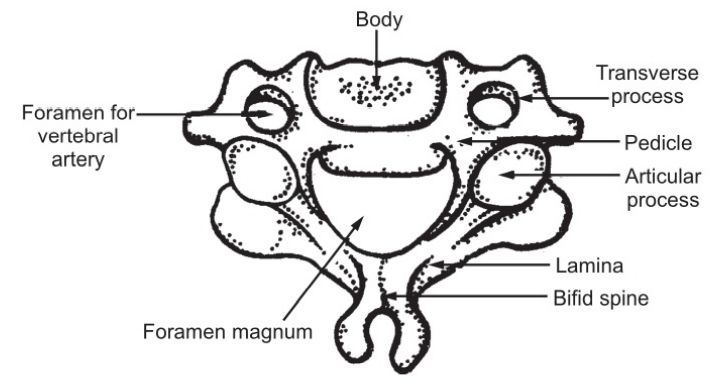

This arch carries three rough processes for muscle attachment. One spinous process projects backward and two transverse processes one on either side. On the superior and inferior surfaces of the neural arch, there are two articular processes (Fig. 1.7), which carry smooth surfaces to articulate with similar processes on the vertebrae above and below. The arch carries a notch on either side on the under surface. The narrow part of the arch above the notch is known as the pedicle (Fig. 1.7). The wide part of the arch carrying the spinous process is known as the lamina, which forms the back wall of the vertebral column. The vertebrae lie body over body and arch, over arch forming a continuous column.

The bodies are joined to each other by thick pads of fibrocartilage called the intervertebral discs. The discs consist of a ring of fibrocartilage and a softer pulpy center called the nucleus. The discs serve to allow slight movement of bone on bone and yet make very strong joints. They also absorb shock to prevent its passage to the brain.

The Cervical Vertebrae:

These are the smallest separate vertebrae with relatively large openings; they run down the neck forming a slightly forward curve.

They have two special features:

- Each transverse process carries an opening through which a vertebral artery passes upwards to the brain.

- The spinous process is forked or bifid giving attachment to muscles and ligaments.

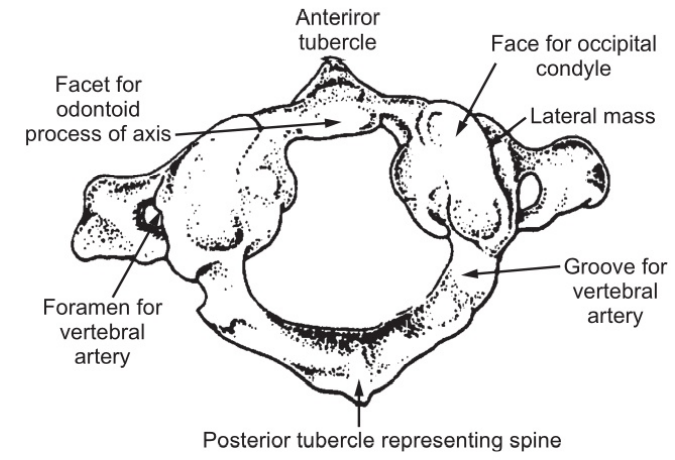

Atlas (Fig. 1.9): It is the first cervical vertebra consisting of a ring of bone with two short transverse processes. The ring is divided into two parts.

- The anterior part is occupied by the odontoid process of the axis which is held in position by a transverse ligament.

- The posterior part is the vertebral foramen and is occupied by the spinal cord. On its superior surface, it has two facets which form joints with the condyles of the occipital bone. The nodding movements of the head take place at these joints.

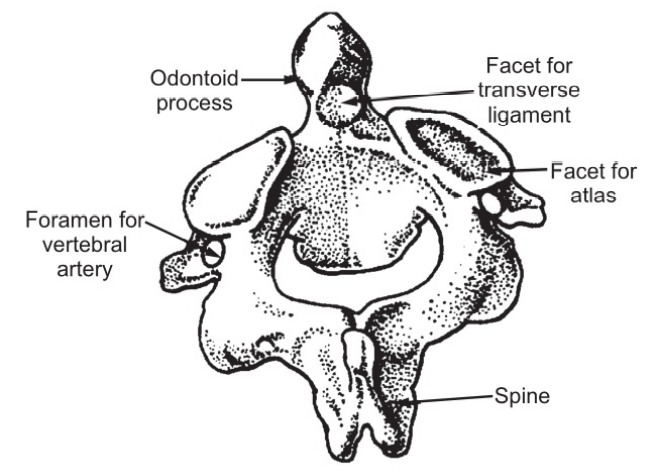

Axis: It is the second cervical vertebra. The body is small and has an upward projecting tooth-like ‘odontoid process’ or the ‘dens’. This process articulates with the atlas (Fig. 1.10).

Other cervical vertebrae are typical. The seventh cervical vertebra does not have a forked spinous process; its process projects considerably and is, therefore, an important anatomical landmark.

The Thoracic Vertebrae

They have two special features (Figs. 1.11 and 1.12):

(a) The spinous processes are long and point downwards so that they partly overlap each other.

(b) Since, the vertebrae articulate with the ribs, they have six facets, out of which four articulate with the ribs.

The heads of the ribs lie between the vertebrae and articulate with one facet on the vertebra above and the other below this vertebra being numbered according to the rib which lies above it.

The Lumbar Vertebrae: The bodies of these vertebrae are the largest and the vertebral foramina are the smallest. The spinous processes are short, flat-sided, and project straight back (Fig. 1.7) giving attachment to the powerful muscles supporting the back.

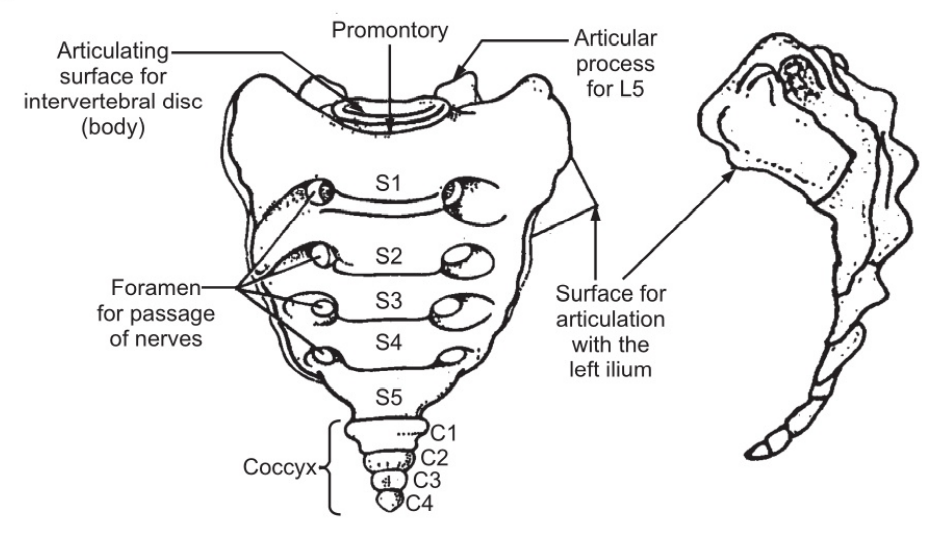

The Sacral Vertebrae:

These are fused to form one bone known as sacrum (Fig. 1.13). This runs down the back of the pelvis forming a backward curve and the upper projecting curve forming the promontory of the sacrum. The upper part of the base of the bone articulates with the fifth lumbar vertebra. On each side, it articulates with the ilium to form the sacroiliac joint and at its inferior tip, it articulates with the coccyx. On each side of the vertebral foramina, there is a series of foramina, one below the other for the passage of the nerves.

The Coccygeal Vertebrae:

Coccyx consists of four-terminal vertebrae fused to form a small triangular bone, the broad base of which articulates with the tip of the sacrum. The movements of individual bones of the vertebral column are very limited. The movements of the column as a whole which include bending forward, backward, sidewise, or turning around are quite extensive. There are more movements in the cervical and lumbar regions than elsewhere.

Functions of the Vertebral Column:

- It provides strong bony protection for the delicate spinal cord lying within it. Spinal nerves, blood vessels, and lymph vessels pass through intervertebral foramina.

- It supports the skull which is protected from shock by the presence of the intervertebral discs.

- It forms the axis of the trunk and gives attachment to the ribs, the shoulder girdle and the upper limbs, the pelvic girdle, and the lower limbs.

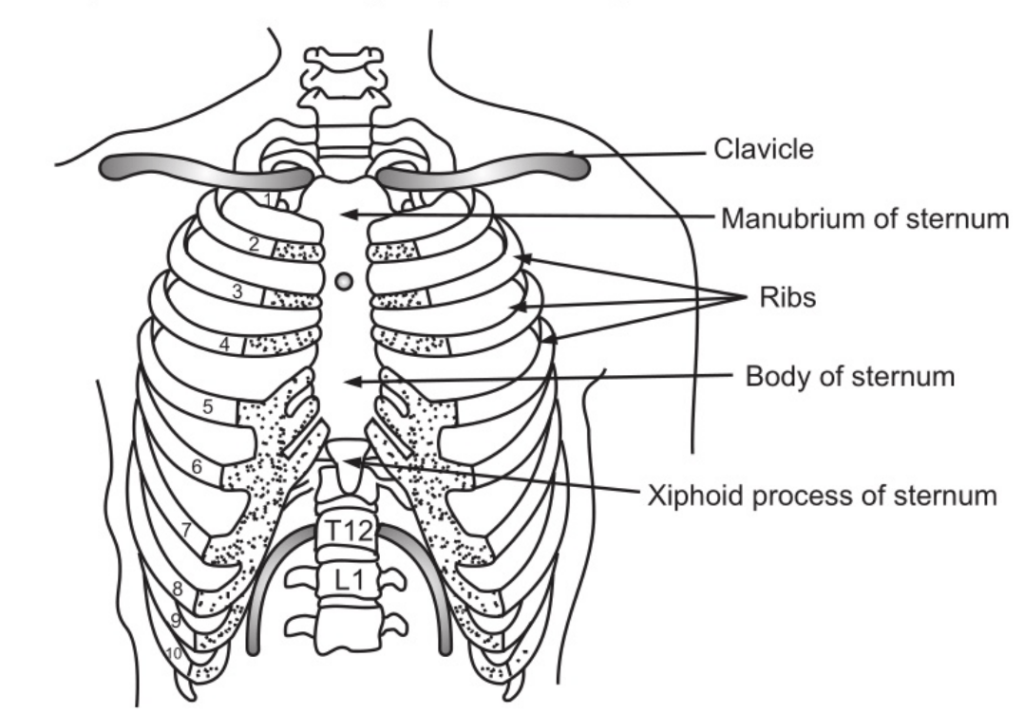

The Thoracic Cage

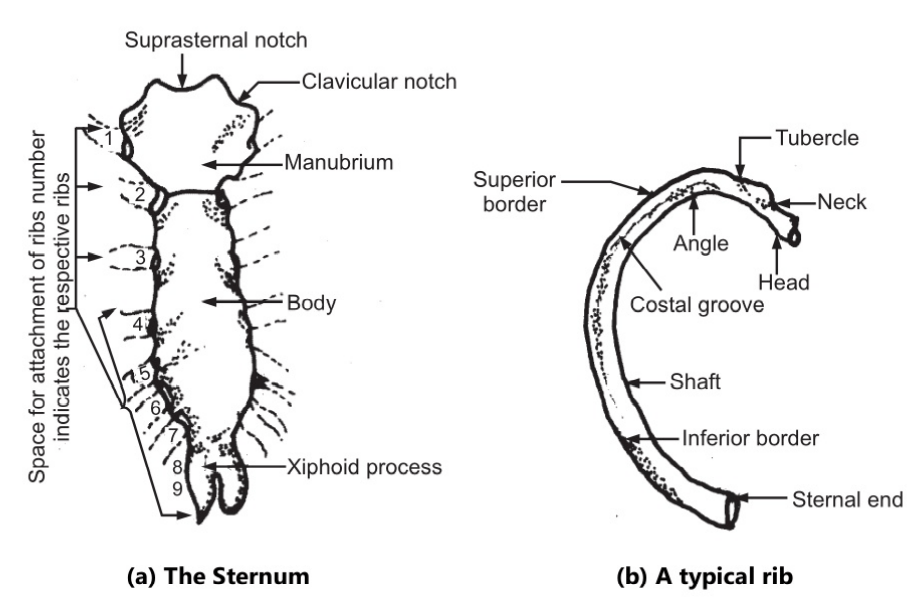

The bones of the thoracic cage (Fig. 1.14) are as follows: 1 sternum; 12 pairs of ribs and 12 thoracic vertebrae. The Sternum [Fig. 1.15 (a)]: It is a flat bone in the middle of the chest. It is shaped like a dragger and is described in three parts.

1. The manubrium is the uppermost part and presents two articular facets on its lateral borders for articulation with the clavicles.

2. The body or middle portion is called gladiolus. It presents facets on the lateral borders for the attachment of the ribs.

3. The Xiphoid process is the tip of the bone that gives attachment to the diaphragm and muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. The process is also called Xiphisternum. The ribs join the sternum by strips of cartilage.

The Ribs

Twelve pairs of ribs form bony lateral walls of the thoracic cage. The first seven are described as true ribs; the eighth, ninth and tenth are called false ribs and the last two are called floating ribs. All the pairs articulate posteriorly with thoracic vertebrae. Anteriorly, the first seven ribs are directly attached to the sternum; the latter three are only indirectly attached to the sternum and the last two pairs have no anterior attachment.

Each rib is a flat curved bone having a head, neck, tubercle, angle, sternal end, anterior and posterior surface, and a superior and inferior border. Fig. 1.15 (b). The head articulates posteriorly with bodies of two adjacent vertebrae. The neck is a constricted portion next to the head and between the head and the tubercle. The tubercle articulates with the transverse process of the thoracic vertebra. The angle is the point at which the bone bends. The sternal end is attached to the sternum by costal cartilage. The superior border is rounded and smooth while the inferior border exhibits a marked groove occupied by blood vessels and nerves. The first rib does not move during respiration.

Spaces between the ribs are occupied by intercostal muscles. During respiration, when these muscles contract, the ribs, and sternum are lifted upwards and downwards increasing the capacity of the thoracic cavity. The ribs increase in size from above to downwards so that the thoracic cavity is roughly cone-shaped. The thoracic vertebrae are described earlier.

Make sure you also check our other amazing Article on: Appendicular skeleton